|

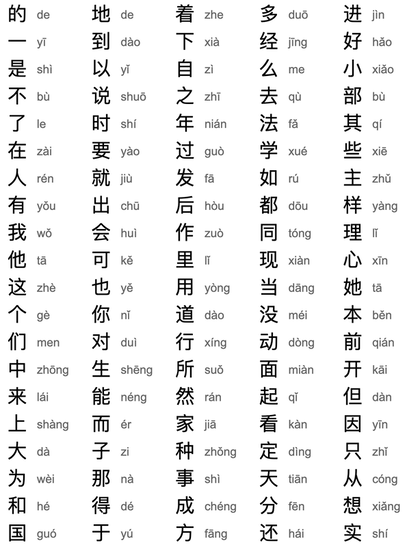

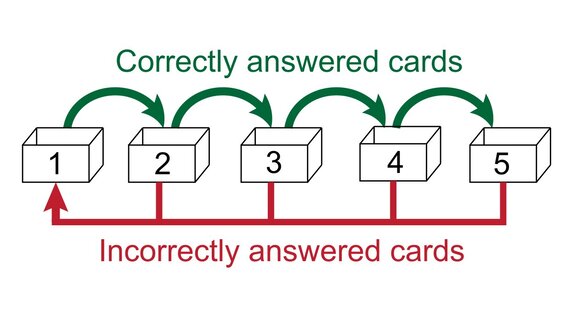

If you want to learn a new language to the point of conversational fluency, take up a new instrument, or learn any new skill at any age, and in a matter of months, then this article will show you how that is possible. Increasing the rate at which you learn new things is like a superpower. It initiates a powerful feedback loop; rapid improvement motivates you to spend more time learning, which in turn leads to more improvement. Using this extraordinary ability to learn quickly can mean the difference between success and failure in any new undertaking. All learning is a form of adaptation. Learning quickly means adapting well. As Stephen Hawking famously said: "Intelligence is the ability to adapt to change." Fortunately, there are many accelerated learning techniques, both old and new, at our disposal to facilitate this adaptation. These techniques allow us to reshape our brains, reset our emotional equilibria, and reimagine our destinies. They can make us more agile, adaptable, and intelligent. Some of these learning techniques are not easy. In fact, many of them require challenge, discomfort, and delayed gratification. But they do work. If you use them, you will have a leg up on your competitors, learn more quickly than your peers, and find that you can surpass many of the targets that you set for yourself. To more effectively illustrate the potential of each accelerated learning technique, I will provide 2 ongoing examples: learning the piano and picking up a new language (Mandarin, for the sake of specificity). 1 — Practice Deliberately Deliberate practice is the systematic development of a skill through immediate feedback, intense concentration, expert coaching, and extending beyond one's comfort zone. It is the hallmark of virtually every advanced performer's routine on the planet. The concept of deliberate practice, originally articulated in Anders Ericcson's excellent book Peak, cuts through many widely believed myths relating to our innate limitations. In his book, Ericcson explains that perfect pitch was long held to be an exceedingly rare inborn talent. However, a study conducted in 2014 by Ayako Sakakibara revealed that an entire group of 24 students between the ages of 2 and 6 were able to learn acquire perfect pitch when trained properly. Generally speaking, if the practice that you are doing is relaxed and enables you to enter a state of flow, it is not deliberate practice. If, on the other hand, you are making mistakes, pushing against the boundaries of your capabilities, and reflecting on your weaknesses in order to refine your training regiment, then you are deliberately practicing. The end goal of deliberate practice is the development of sophisticated mental representations. These are internalized models of a particular movement, concept, behaviour, or chunk of information. If you are learning the piano at a beginner or intermediate level, deliberate practice means taking on a challenging new piece or warm-up that stretches your limits. You or your piano teacher might take note of such things as: number of mistakes made, playing speed, and any particularly difficult sections. You could then target the difficult portion, and methodically increase playing speed, focus, and decrease the number of errors. This is a far cry from playing your favourite song over and over again, which is highly enjoyable(and encouraged), but not ideal for improving quickly. For learning Mandarin, deliberate practice might mean: 1) using spaced repetition software like Anki, 2) incorporating new vocabulary and phrases into real conversations, 3) having a private tutor offer feedback on pronunciation and tones while encouraging risk-taking, and 4) using mnemonic devices to remember difficult words. 2 — Make Errors in Order to Stimulate Neuroplasticity One of the biggest impediments to learning something new is the fear of being imperfect and making mistakes(I looked it up; it's called atelophobia). It is our fear of failure that keeps us from starting new endeavours and persisting at them. Ray Dalio, the founder of Bridgewater Associates and author of Principles, writes: "Everyone fails. Anyone you see succeeding is only succeeding at the things you’re paying attention to—I guarantee they are also failing at lots of other things. The people I respect most are those who fail well. I respect them even more than those who succeed." New research shows that not only is failure an important part of the learning process, but it actually speeds up learning through rapid neurophysiological change, also known as neuroplasticity. Errors that stem from a mismatch between our models of the world and the feedback we receive trick our nervous system into adaptation. When we practice challenging activities and make frequent errors, our brains don't don't know what to do. The circuitry that is in place is insufficient to handle the present degree of difficulty. And so, the brain produces a cascade of chemicals like epinephrine, acetylcholine, and dopamine that begin rewiring the neural circuitry. Andrew Huberman, a professor in the department of Neurobiology at Stanford University, discusses this phenomenon at length in his provocative podcast lecture: “The signal that generates the plasticity is the making of errors. It’s the reaches and failures that signal to the nervous system that this is not working, and therefore the [desired] shifts start to take place.” He then outlines the evolutionary nature of our nervous systems, and how errors force us out of homeostasis and towards growth: “Errors are the basis for neuroplasticity and for learning [...] humans do not like this feeling of frustration and making errors. The few that do, do exceedingly well in whatever pursuits they happen to be involved in. The ones that don’t, generally don’t do well. They generally don’t learn much. And if you think about it, why would your nervous system ever change? Unless there was something to be afraid of [...] or there’s an error in our performance.” (emphasis mine) The fact that errors trigger neuroplasticity is a groundbreaking revelation. The simple act of repeatedly making mistakes during practice triggers a state that is immensely conducive to learning. What's more, Huberman suggests that this receptive state carries over even after a learning session has ended. We can use the momentum that our mistakes create to learn multiple skills in succession, and achieve more progress in all of them. To apply this technique to piano practice, take a challenging part of a song and perform it repeatedly. Notice the errors you make; don't worry about rendering the piece perfectly. You will feel frustration and discomfort. This means you are beginning to tap into that state of heightened neuroplasticity. For learning Mandarin, engage in a conversation above your level of competency with a willing, patient partner. Use new and unfamiliar terms and expressions. Write down characters for the first time. It shouldn't take too long before a sense of irritability sets in. This is a good sign; your brain is processing errors and attempting to improve the quality of your mental representations. 3 — Associate Resistance with Reward This accelerated learning technique dovetails with the previous one. When inevitable feelings of frustration, irritation, and strain arise during the process of practice, we are faced with a choice; we either continue to struggle, or throw in the towel. Continuing to learn in the face of heavy resistance is the first victory. Understand: there is a bit of mental jiu-jitsu that we can perform at this crucial point if we keep going. Instead of fighting the resistance and wearing ourselves out, we can actively recognize the role that frustration plays in speeding up our self-education and development. We can use the resistance as evidence that we are on the right path towards optimal learning. When I feel particularly strained during a practice session, I often conjure up phrases like: "I am moving in the right direction" and "the obstacle is the way". These thoughts help me to keep in mind that the struggle is an essential part of the learning process. The more we associate the challenges of resistance with the rewards of progress, the more we tap into the dopaminergic systems that make us feel focused, interested, and happy. This association is not masochism. It is fundamentally altering our relationship with the struggle and discomfort of growth. The upshot of this association is that we begin to crave new, difficult learning experiences. The struggle actually signals the onset of exciting progress. We learn to lean into friction, and embrace the suck. If you are learning piano, the wrong notes that make you want to pull your hair out are opportunities to develop a more constructive relationship with errors. You are entering a space where mistakes trigger brain plasticity. For learning Mandarin, the process is the same. Repeated errors in speaking, listening, writing and reading are prepping your brain to be reshaped. 4 — Use Rest and the NSDR Protocol One of the greatest underused learning tools actually doesn't involve active learning at all. Research from a recent NIH study showed that periods of short rest between learning bouts resulted in brain wave changes that consolidated memory and improved performance. These changes occurred even when the rest periods were only seconds long. Leonardo G, Cohen, a medical researcher at NIH's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke(NINDS), weighs in on this powerful phenomenon: "Everyone thinks you need to 'practice, practice, practice' when learning something new. Instead, we found that resting, early and often, may be just as critical to learning as practice". This research established that taking frequent micro-breaks can help your brain process and encode new information. But what about longer, 10 to 20 minute breaks? Another recent study, this one published in the prestigious science journal Nature, demonstrated that participants performed better on a memory test when they had a ten minute rest period, compared to another group that engaged in an unrelated task for ten minutes. Non-Sleep Deep Rest, or NSDR, is the practice of quickly entering into a state of relaxation on the cusp of sleep. Popularized by Andrew Huberman, NSDR is a great way to quickly recuperate after a learning session. Furthermore, there is evidence that the brain replays previously learned movements and sequences during these protracted rest periods. A piano player might leverage the power of brief rests by pausing between attempts of a particularly difficult section. At the end of an hour-long practice session, the pianist could lie down and listen to a 15 minute guided meditation, or close her eyes and practice a relaxation technique for a similar amount of time. The Mandarin learner could do the same, taking micro-rests during a conversation, and listening to ambient music with a face mask on after running a gauntlet of intense practice. 5 — Keep Learning Sessions Short Frequent, extended periods of work without breaks or rest are a recipe for burnout. After more than 2 hours of continuous practice, our brains struggle to concentrate, frustration may turn to exasperation, and progress usually grinds to a halt. For most tasks, 15-45 minutes of uninterrupted focus can yield incredible benefits. Whether you are learning how to code, studying for a biology exam, or practicing a new sword-swallowing technique, a chunk of time in this window works perfectly. However, some activities, like writing or painting, have high time-related start-up costs. It may take upwards of 30 minutes just to get into a flow state, where you are making steady progress and have overcome the initial hurdles of generating focus and creativity. I personally spend 35 minutes working or learning, followed by 5 to 10 minutes of deep rest. This method is known as the Pomodoro technique, which I recommend highly. You can manipulate the time settings on the website to suit your needs. The optimal work-rest balance will be determined by your individual preferences and learning objectives. Experiment with different times to find what works for you. When learning piano or Mandarin, play around with the amount of practice time. Ideally, keep it under 45 minutes. There is nothing stopping you from having multiple practice sessions throughout the day, interspersed by intentional rest periods. If you feel like supporting this blog, click on this link and grab a visual timer to put on top of your piano or desk. Having a physical, analog timer that doesn't have an Instagram feed or show you cat videos is great for deep, distraction-free practice. 6 — Try the Feynman Technique This technique involves taking out a piece of paper and writing down your current understanding of a concept, subject or idea. However, there's a catch: you have to explain it, and teach it, in the simplest possible terms, so that even a 12 year old child could understand it. After you have written down the details of the idea/concept/subject, look for any areas where there are holes in your knowledge. Are you missing key elements? Oversimplifying? Glossing over too much material? Then, you can go back and iterate, until you have a polished version of an explanation. The reason this technique works so well is that teaching something reveals which parts we don't know. My own experience as a teacher has led me to a much deeper understanding of literature and psychology. I had to have a firm grasp of the novel or psychological concept I was teaching in order to convey it to my students. I also realized how little I actually knew about topics I thought I had a firm grasp on. When learning the piano, music theory plays an important role. You could take one aspect, like the circle of fifths or chord structures, and explain it in the simplest terms possible using the Feynman technique. Then, you might identify which areas are missing or inaccurate, do some research online, and keep adding details until your explanation matches the expert one. For a really fun example of how complex musical concepts are explained at different levels of understanding, here's a great video featuring Jacob Collier and the legendary Herbie Hancock. For Mandarin, you could do something a little different: try explaining a very basic concept, like directions, without using English. Which characters do you stumble over in speech? Write down incorrectly? Forget completely? Then, go back and review the words and phrases, and revise. For a more detailed account of the Feynman Technique, I highly recommend Shane Perrish's article at Farnam Street. 7 — Apply the Pareto Principle In 1896, economist Vilfredo Pareto observed that approximately 80% of the wealth in Italy was owned by 20% of the population. Soon after he published his findings in his work Cours d'Économie Politique, Pareto and others noticed that this unequal distribution rule applies in many other domains: agriculture, education and marketing, to name a few. This principle is now known as the 80/20 Rule. For our purposes, it is important to note that roughly 80% of the results from any learning undertaking come from 20% of the work we put in. And, conversely, about 80% of the practice only yields 20% of the results. We can optimize our learning significantly by focusing our efforts on the 20% of the system that gives us 80% of the skills and/or understanding. Following the path of Pareto Efficiency is critical to learning any new subject, skill, or language quickly. For piano, shift your focus away from the 88 keys, myriad modes, and complex harmonies. Take the basic building blocks: 7 notes in a scale, and basic chord structures. For example, if you know that a major chord has three semitones (i.e. keys) between the first and second note, and two semitones between the second and third note, you can then construct 12 major chords (or many more if you include octaves). For Mandarin, you can take a similar approach by first identifying the 100 most commonly used characters, and 10 most commonly used phrase structures in the language. "Overlearning" these aspects of the language, which means practicing them past the point of making noticeable progress, will help you get 80% out of the system with less than 20% of the work, and in less than 1/5th of the time. 8 — Shift Towards an Optimal State of Performance Athletes and other peak performers alter their physiological state through practices like meditation, breathing exercises, warm-ups, and motivational thinking. Why not take advantage of these tools to enter into an ideal state for learning? There are many sub-optimal states that threaten to undermine your learning efforts, such as distraction, hyperactivity, and fatigue. Whether you require the ability to focus on a single problem and solution (convergent thinking) or the ability to think more openly and consider a variety of possibilities (convergent thinking), choosing the right techniques to prime your mind can make a huge difference. Consider the idea of returning to a state of equilibrium. Do you find that you are too jittery, stressed or nervous to continue a prolonged learning task? Try taking slow deep breaths using box breathing, or use the power of intentional sighs to offload carbon dioxide and reduce stress (researched by Andrew Huberman). Simply take two quick inhales through the nose, followed by a long exhale through your mouth. Do this 5-6 times, and you will probably notice a profound shift in your mental and physiological condition. If you are feeling too exhausted, inattentive, or unmotivated, a short burst of exercise or a quick round or two of Wim Hof breathing can help you restore your mental acuity. Jonathan Waitskin describes the experience of coming up against a wall of fatigue during chess tournaments in his book The Art of Learning. Some of his games would take several hours, with a single move requiring 20-30 minutes of intense, unbroken concentration. When he felt like his judgment and attention were slipping, he would go splash some water on his face, or run up and down 3-4 flights of stairs, before returning to the chess match. This routine of physical movement invigorated him and altered his state enough to bring him back into the game. If you are exhausted while practicing the piano, try a 5-minute run around the block or do 30 jumping jacks. If you have had a few too many coffees before your Mandarin lesson, try a short meditation session or some deep breathing to activate your parasympathetic nervous system and enter a state of more relaxed alertness. 9 — Use Spaced Repetition and Retrieval Spaced repetition involves repeatedly drilling vocabulary, content or concepts, with longer and longer intervals between testing. For example, when you are learning piano you might have a cue card (Anki works well here) with the phrase "minor chord" on it. When you encounter that particular card, you provide an explanation of the concept. If the explanation is accurate, the card would go to the back of the set and you wouldn't test yourself on it for a few days/weeks. If the explanation is inaccurate, the card would go to the front of the set and you would test yourself on it sooner. The process of using spaced repetition in this way is known as the Lietner System, and looks something like this: Passively reading or practicing doesn't lead to the significant learning leaps that occur when you use spaced repetition. This is because testing periodically helps us to overcome our tendency to forget things at an exponential rate, which then tapers off over time (for more on this, check out Ebbinghuas's Forgetting Curve) Spaced repetition works best in conjunction with retrieval, sometimes known as recall. Scott H. Young, in his book Ultralearning, refers to the act of retrieving information in order to test oneself as "one of the most powerful methods known to build a deep understanding." The reason for this may be simple: it's hard. Professor Robert Bjork coined the term desirable difficulty to refer to learning strategies that feel strenuous and filled with mistakes in the short-term, but which lead to greater retention of the material in the long-term (see accelerated learning tool #3). Retrieval lies in direct contrast to passive reading, which provides the illusion of knowledge but little to no retention of learning. If you are learning Mandarin, try practicing free recall. How many characters can you remember, write down, and pronounce? What basic information from a book or movie can you retrieve from memory and use in speech? Whatever you do, avoid looking up the information until after you are finished! The temptation will be great to take a peek at the right answers, but doing so will undermine your efforts at retrieving and reproducing the language yourself, and stifle your progress. 10 — Reflect on Your Learning Progress and Goals John Dewey, the 20th century psychologist and educational reformer once wrote, "we do not learn from experience... we learn from reflecting on experience."

You can play hundreds of chess games and not get any better at chess. You can play the piano all you want, but you won't improve unless you have goals and reflect on the process. I find daily journaling invaluable for the simple reason that I get to reflect on what I learned well, and where I stumbled along the way. Knowing what to improve on and what to change comes almost effortlessly when you sit down every night and put your day up for review. Journalling also has the added benefit of allowing you to consolidate new learning by retrieving it and processing it again. There are many ways to reflect on your learning. Keep a daily learning log that tracks your progress as well as your daily/weekly/monthly targets. Try carving out 20 minutes in your day just for thinking about what works and what doesn't with your current practice/writing/working regime. You can also use an application like Clockify to timebox your schedule and write notes after each study or work session (warning: this will also enhance your productivity more generally). Whatever you do, don't put it on a to-do list. It probably won't get done. For learning Mandarin or piano, measuring your forward movement is key. Reflect on your biggest obstacles toward advancement. Write down your struggles to pick apart, and triumphs so that you can keep going. Final Thoughts By implementing these 10 accelerated learning tools, you will learn far more optimally, and free up considerable personal time. You will retain more, understand more, and be able to do more with what you learn. I am a firm believer in the idea that there are virtually no limits to human potential; the only limits are the ones we impose upon ourselves. By acquiring skills and wisdom more actively, efficiently, and intentionally, we can set ourselves up to move in the direction of our loftiest dreams and ambitions. Good luck on your next learning adventure! Comments are closed.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed