|

Mental models are essential for improved decision-making, clearer thinking, and a deeper understanding of reality.

Having access to high-quality mental models can yield long-term success in business, academics, and personal life. They are the tools that moguls like Warren Buffett, Elon Musk, and Peter Thiel have used to build their billion-dollar companies. Without further ado, let's dive right in and cover what mental models are, how they work, some key examples of mental models, as well as some further reading on the topic. What are Mental Models? 9 Key Models 1) First Principles Thinking 2) Thought Experiments 3) Diminishing Returns 4) Process vs. Outcome 5) Inversion 6) Fixed vs. Growth Mindset 7) Compounding 8) Iteration 9) Skin in the Game/Incentives Further Reading

What are Mental Models?

Mental models are chunks of information from different disciplines that help us map out our understanding of the world. They are thinking tools you can apply to a nearly infinite array of choices and problems, from whom to marry to what to eat for dinner tonight (note: the correct answer to #2 is tacos). Mental models help you unravel the complexity and uncertainty of reality, so that you can separate what is useful and true from what isn't. They act as information filters, helping you focus on the most salient parts of a problem. Because we can't fit every conceivable fact and detail about the world into our brains (unless you're Mark "Replicant" Zuckerberg) we have to simplify things. We need short, comprehensible ideas that can explain a lot for us. Imagine a baseball field photographed from many different positions. Each photograph is different, and reveals unique parts of the field. None of the photographs can capture the exactness of the field as it is. But, together they offer lots of useful information about where the bases are, what the dugouts look like, and how much distance there is between the outfield and the infield. Shane Parrish, in his book The Great Mental Models Vol. 1, offers an excellent description of how these different perspectives often get compartmentalized: “An engineer will often think in terms of systems by default. A psychologist will think in terms of incentives. A business person might think in terms of opportunity cost and risk-reward. Through their disciplines, each of these people sees part of the situation, the part of the world that makes sense to them. None of them, however, see the entire situation unless they are thinking in a multidisciplinary way. In short, they have blind spots.” At their core, mental models are about uncovering and eliminating these blind spots, in order to see situations as clearly and accurately as possible.

9 Key Mental Models

Now that we've covered what mental models are in broad terms, let's take a look at nine essential mental models and how they work, so that you can begin to apply them to real-world situations.

1) First Principles Thinking

Thinking from first principles is one of the most powerful tools for understanding reality. Elon Musk is notorious for using this model to deconstruct problems and arrive at solutions no one else thought were possible. For example, many experts claimed that the cost of batteries would remain relatively stable over time. This presented a problem for Musk, who needed large numbers of batteries for his fleet of electric cars. Instead of being daunted by its intractability, Musk broke the problem into its fundamental parts. He asked a series of questions that demonstrated what first principles thinking is all about: What are batteries made of? What is the spot price for each of those materials? How can batteries be creatively and efficiently assembled? The answers to these questions revealed that you could make batteries for a fraction of the assumed cost. While most experts reasoned by historical analogy, which is a flawed mental representation, Elon used deeper, physics-based reasoning. The beauty of mental models lies in their flexibility. You can apply first principles thinking to virtually anything. A common question in philosophy is: "what does it mean to live a good life?" Many conversations — I know from experience — have spiralled down this rabbit hole of vague prescription. However, lives can be broken up into years, months, weeks, and days. Asking "what does a good day look like?" is a more tangible and actionable question. Does your ideal day involve lazing by the beach, drinking daiquiris and slowly slipping into a tropical coma? Or does it involve practicing your gymnastics routine for ten hours a day to compete in the next Olympics? The answer to these questions will shape the type of life you end up leading—and probably affect how well you perform in the next Olympics. Here are some other questions you can ask to design a life from first principles:

2) Thought Experiments

When you are faced with a problem that is both intangible and difficult to replicate in real life, a thought experiment can help you test out relevant scenarios. Using your imagination, you can add or remove variables while simulating different outcomes. Let's say you are wondering how a product launch will go. You can project forward six months and visualize the outcome. What are consumers saying about the product? What problems do they have with it? Was it successful? Why or why not? What would happen if you held your product launch in a different venue? Invested in more PR? Leveraged a personal connection for more publicity? What would happen if you staged the product launch on the moon? It's theoretically possible. (I knew first principles thinking would come in handy). Such experiments can help you pinpoint flaws and highlight positive features, while giving you valuable information. The best thing about thought experiments is that there are virtually no costs. You can run them as often as you want, and explore all the different strands of a problem from your desk chair(or the beach).

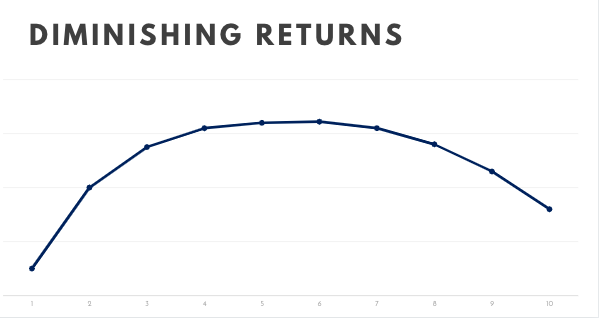

3) Law of Diminishing Returns

You can get a lot out of a system initially. But, in many areas, the more progress you make, the harder it becomes to make additional progress. Productivity is a perfect example. If you go from being unscheduled to following a detailed calendar, you quickly gain an hour or two of work time each day. If you listen to podcasts while cleaning or cooking, you unlock the potential of "found" time, and are able to learn significantly more after weeks or months of continuing the habit. However, it becomes increasingly challenging to make significant headway after implementing basic scheduling hacks(what you might call the "low hanging fruit"). If your productivity is near-optimal, you might spend an hour trying to squeeze a few minutes of productive time out of your schedule. At a certain point, the costs outweigh the benefits, and you can actually start to see negative returns on your efforts. Diminishing returns can be applied to many different disciplines: sports, weightlifting, the correlation between wealth and happiness, and economic production, to name a few. You can use this mental model to decide which areas you want to optimize, and when to refocus your energy on new, unexploited avenues.

4) Process vs. Outcome

In a world that is so intensely focused on short-term results, being able to think in terms of processes and systems can offer you huge long-term advantages. The stock market is notoriously fickle in the short term. Immediate earnings are all that matter to many companies and investors. Stock prices of well-managed companies can plummet based solely on rumours of poor quarterly performance. An intelligent investor like Warren Buffett trusts the process. He is aware of what he knows and what he doesn't know. He makes decisions based on his circle of competence, and then considers his choices in terms of decades, not hours. In his fantastic book Atomic Habits, James Clear writes: "You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems." The process you follow allows you to maintain consistency and achieve success in spite of what the immediate outcomes may suggest. If your goal is to write a book, your process might be to write 500 words a day. As long as you reach that daily target, you can trust that you are making forward progress.

5) Inversion

Many people keep a to-do list. But, evidence suggests that to-do lists don't really work. However, Tim Ferriss notes that not-to-do lists work much better. They prevent distractions, keep you accountable, and enhance your productivity. This is a prime example of inverted thinking. By taking something customary and flipping it on its head, you can often learn unexpected things and see problems in very different ways. Mathematicians use inversion by starting with the answer and working backwards. Investors use inversion by figuring out how to avoid losing money. Artists use inversion to determine what details might be removed from a painting in order to improve it. The famous 19th century German mathematician Carl Jacobi famously said "muss immer umkehren", which, according to my spotty German, roughly translates to "invert, always invert." Entrepreneurs love using inverted thinking to uncover new opportunities and develop contrarian points of view. What consumer needs are businesses not meeting? What secrets might still be out there? What if monopoly is actually a force for innovation, while competition hinders it? Here are some questions that may help to prompt some inverted thinking:

6) Fixed vs. Growth Mindset

Mindset plays a decisive role in learning and success. It offers an excellent framework with which to understand people's responses to setbacks, challenges, and opportunities. From a fixed mindset perspective, challenges threaten your intelligence, limitations are concrete, and the judgment of others matters above all else. From a growth mindset perspective, obstacles are opportunities to grow and persevere, the brain is capable of almost any adaptation or learning, and progress matters more than what people think of you. In reality, these two categories are not mutually exclusive. People bounce back and forth between fixed and growth mindsets, depending on the activity and environment at hand. As a mental model, mindset thinking can help steer you towards growth-oriented action, as well as lead you to question assumptions about your capabilities and potential. Some examples of growth-mindset behaviour include: choosing the more challenging option, actively seeking out feedback and criticism, working hard for delayed rewards, and being skeptical of self-limiting stories.

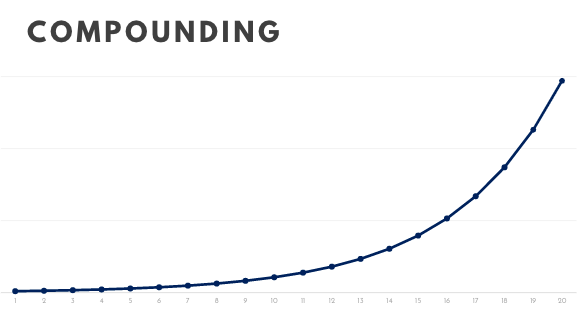

7) Compounding

Investments don't just grow at a linear rate every year. The interest that accumulates joins the principal, and that interest begins to generate interest as well. Over the course of two years, it doesn't look like much. But after ten, twenty, or thirty years, it grows to an astonishing amount. The idea of compounding doesn't only apply to money. It is a highly flexible mental model that you can use to leverage exponential growth. As investor and entrepreneur Naval Ravikant says, “All the returns in life, whether in wealth, relationships, or knowledge, come from compound interest.” Compounding can help you overcome what James Clear refers to as the Valley of Disappointment. At the beginning of a project, it may feel that you are putting in a ton of leg work and not reaping any significant results. Many hours of work may only yield you a handful of views, or likes, or products sold. However, as the amount of work grows, the results eventually catch up. The same applies to learning. Each new concept builds on previous understanding. If you keep learning new things, you end up with a sophisticated framework of ideas with which to make high-quality decisions. 8) Iteration The greatest paintings, plays, books, and songs are not the results of single, isolated efforts. They are the products of many, many iterations over time. When you make or design something near the limit of your current abilities, you are honing your craft. You are entering into the realm of creativity. It sounds simple, but if you want to get better at music, writing, or painting, you need to play music, write, and paint. A lot. Each song, page, or picture is a self-contained cycle that feeds into the next one. Creating a product helps you to internalize the rules of good design, planning, and execution. Iteration is the ideal mechanism of progress. This is not merely the repetition of an action with the hope of getting better. It is the process of taking what you have learned with you to the next task, so that you can do it marginally better. Ultimately, iteration can help you leverage the power of a virtuous circle.

9) Skin in The Game / Incentives

People are highly motivated to defend institutions, beliefs, and ideas when there is something at stake. The engineer who receives stock options as a bonus is more likely to support the long-term interests of a company than the engineer who receives only cash. Incentives can promote ethical behaviour and rally people towards a particular cause. Or they can doom a project, product, or company. As such, skin in the game can be both a blessing and curse. A new doctor who has trained for ten years and spent half a million dollars on her education will desperately try to avoid malpractice. Likewise, the downside of being delicensed far outweighs the benefit of accepting bribes, so she likely won't accept one. However, these sunk costs may also make her more risk-averse. Questioning medical authorities and procedures in order to discover better alternatives could end her career. She may feel compelled to maintain the status quo Side note: the sunk cost fallacy, loss aversion, and status quo bias are three highly useful mental models in their own right. Determining who has skin in the game and who doesn't can help you figure out who to work with, and decide on the best course of future action. Trust, reputation, and long-term commitment are signs that a person, or company, has the right incentives. When in doubt, ask, "cui bono?" "who benefits?" This will usually reveal what kind of actors you are dealing with.

Further Reading

By no means does this article offer an exhaustive list of mental models. There are many more out there to explore, try out, and assess. Remember: these mental models are not reality. They may be faulty, incomplete, and limited in their uses.Using more, and better, mental models will reveal a more accurate picture of reality.

Comments are closed.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed