The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.”

Linkedin Learning (formerly Lynda.com) offers more than 14,000 online courses that fall into three broad categories: business, creativity, and technology. Many of these courses are geared towards developing new, in demand skills, such as coding, marketing or web design.

Whether your goal is to generate more business ideas, figure out how to get new ideas for your writing, or just have better ideas in general, the State Shift Technique works.

With that, let's dive right in and start with a story. Discovery In August of 1928, at St. Mary's Hospital, the celebrated medical researcher Alexander Fleming was working on a strictly academic problem. His task was to identify and isolate different strains of the bacteria Staphylococcus Aureus. There was no promise of any groundbreaking discoveries or historical legacy. In fact, it was a rather straightforward process of cataloguing and classification. And so, Fleming did what any creative, respectable scientist would do when faced with a drawn-out stretch of work. He went on vacation.

Mental models are essential for improved decision-making, clearer thinking, and a deeper understanding of reality.

Having access to high-quality mental models can yield long-term success in business, academics, and personal life. They are the tools that moguls like Warren Buffett, Elon Musk, and Peter Thiel have used to build their billion-dollar companies. Without further ado, let's dive right in and cover what mental models are, how they work, some key examples of mental models, as well as some further reading on the topic. What are Mental Models? 9 Key Models 1) First Principles Thinking 2) Thought Experiments 3) Diminishing Returns 4) Process vs. Outcome 5) Inversion 6) Fixed vs. Growth Mindset 7) Compounding 8) Iteration 9) Skin in the Game/Incentives Further Reading If you want to learn a new language to the point of conversational fluency, take up a new instrument, or learn any new skill at any age, and in a matter of months, then this article will show you how that is possible. Increasing the rate at which you learn new things is like a superpower. It initiates a powerful feedback loop; rapid improvement motivates you to spend more time learning, which in turn leads to more improvement. Using this extraordinary ability to learn quickly can mean the difference between success and failure in any new undertaking. All learning is a form of adaptation. Learning quickly means adapting well. As Stephen Hawking famously said: "Intelligence is the ability to adapt to change."

Whether you are looking for creative solutions to market your business, improve your creative writing/storytelling, come up with material for your first stand-up comedy gig, or achieve virtually any other goal, there is a method that can help dramatically.

I used to think creativity was inborn. Some people have it, some people don't. It's only recently that I have begun to realize how dead wrong I was.  Photo by Museums Victoria on Unsplash Letter writing, like knot-tying and full-contact finger puppetry, is a lost art form.

Before smartphones, computers and email, letters were a common way to show the important people in your life that you cared about them. The time it took to find the space and materials necessary, arrange your thoughts, put them down on the page, seal the envelope and mail it off meant that you valued someone greatly. But, letter writing is more than just a quaint, old-fashioned practice. Recent studies show that writing things down by hand leads to increased activity in the parts of the brain that are associated with learning.  Photo by Clark Young on Unsplash Whether you want to become a great writer, a successful business owner, an innovative graphic designer, or develop high-level skills in some other discipline, the principles that underlie the path to mastery are the same. These hard-won principles can be learned, instilled, and taught to others. About seven years ago, I had the opportunity to explore Borneo during a long-anticipated, three week sojourn from my long-term teaching stint in Taiwan.

The jungles were lush, the orangutans breathtaking, and the nearby waters were the embodiment of picturesque, cerulean brilliance. And yet, at times, something didn’t seem quite right. I couldn’t put my finger on it. I was agitated and anxious. During one particularly scenic sunset on an elevated walkway in the rainforest, I felt downright despondent. Why? This was supposed to be a majestic escape from all of the undesirable elements of city life: pollution, crowds, work, responsibility. There was something missing. Was it that I was a solo traveler? That could be. But I’d traveled quite a bit by myself by that time, and didn't always feel this way. It is only now, in the glorious, truth bearing light of hindsight, that I fully understand what was wrong. I hadn’t clearly defined my own values. During that trip, I met lots of people, saw tons of incredible sights, and ate prolific quantities of exotic foods. It was a feast for the senses. And yet, it didn’t have any deep, underlying meaning. Lots of fun, but not purposeful. If I had to articulate what my values were then, I’d say they were: freedom, pleasure, novelty, comfort, and being liked. What do all these values have in common? All of them are externally-oriented. None of them are, or were, in my control. Enter social anxiety and chronic dissatisfaction, stage right. It wasn’t until I stumbled upon excerpts from The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck by Mark Manson many years later that I realized how important values can be. Oddly enough, at the time I was actually living pretty much in accordance with my values. But since they were terrible values, the outcome could never meet my expectations. Which leads us to the question: how do you know which values are good and which are bad? Mark Manson writes: “Good values are 1) reality based 2) socially constructive, and 3) immediate and controllable. Bad values are 1) superstitious, 2) socially destructive, and 3) not immediate or controllable [...] Some examples of good healthy values: honesty, innovation, vulnerability, standing up for oneself, standing up for others, self-respect, curiosity, charity, humility, creativity. Some examples of bad values: dominance [...] feeling good all the time, always being the center of attention, not being alone, being liked by everybody, being rich for the sake of being rich, sacrificing small animals to the pagan gods.” Life right now may be filled with suffering, struggle, and difficulties. You may even feel compelled to sacrifice animals to the gods sometimes. But, if you have the right values, the burden of the present can get a little lighter—your vision of the future, a little clearer. In short: once you change your values, your values change everything. What are your values? Spend some time thinking about them. Review them. Write them down. And then carry them with you, in your heart and in your mind, whatever happens. Everybody knows the dice are loaded. Everybody knows the ship is sinking.

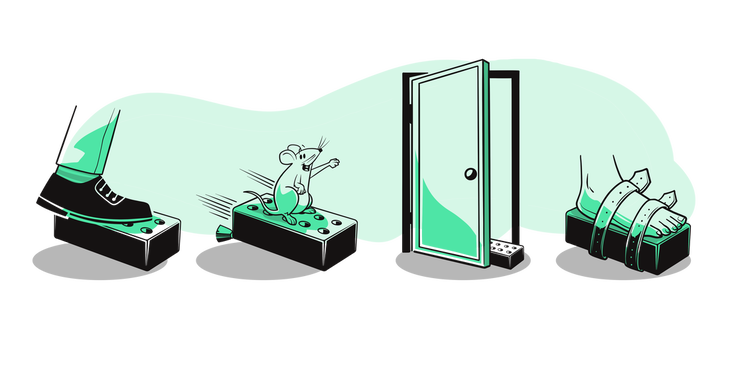

But there is still time. You’ve got this song, this book, this idea, this passion project inside you that wants to come out into the world and take shape. The only things in the way are excuses and self-limiting beliefs. They are comforting, because they mean that you don’t have to make any mistakes or slip-ups. If you hold onto them, you can go on thinking that all those other people who made their mark—or who quietly worked on their practice with determination and discipline—had some inborn talent, ability, or intellect. They made mistakes, but that didn’t stop them. They persisted. They made it their mission to show up every day, and work on their craft. So, forget your perfect offering. There is a crack, a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in. It’s now or never. Significant goals, like completing a work project, writing a book, or buying a home, can seem pretty daunting. And, if we come across a few too many obstacles— especially if they are unexpected—we may end up scaling down our ambitions, or throwing in the towel entirely.

A common way to make large goals seem more attainable is to break them down into chunks—often referred to as micro-goals— and work towards completing them one stage at a time. This is a fantastic way to frame objectives. After all, work projects really are just a collection of executable tasks, writing a book happens a few pages at a time, and buying a home involves money-saving habits that span over years, if not longer. However, there is a little-known tool that is even more effective at making you persevere towards your goals, accomplish more and enjoy the process. Enter the dopamine reward system. It is the brain’s way of neurochemically promoting certain behaviours while curbing others. Without entering into the murky depths of neuroscience too deeply, let’s focus on the real, life-changing insight: the way our brains process rewards can be manipulated—rewired, so to speak—to suit our aspirations. This is a big deal. In the words of Dr. Andrew Huberman, “The ability to control internal reward schedules is everything”. We control these reward schedules through our thinking, and, through training, we can link rewards to the effort, instead of the outcome. The challenges. The grind. The obstacles we face along the way. The pressures, stress, and discomfort of work. These can become signs of forward progress, of advancement and improvement. The secret to activating our dopamine reward systems through effort involves noticing and reflecting on incremental—even miniscule—progress towards a goal. You ran 2 minutes more than yesterday—that means you are on the right path. You showed up and wrote a page in your journal even though you didn’t feel like it? That means you overcame resistance and prevailed. You didn’t lose your cool when that person cut you off? You just moved in the direction of patience and tolerance. It all starts with a process I call thought-pairing. First, notice something related to effort. Then, reflect on how it brings you closer to your desired identity. The possibilities and uses that this technique creates are essentially limitless, but here’s an example. Imagine you suffer from debilitating shyness. You want to become more courageous when it comes to being social, instead of being avoidant like your former self. You start with a small gesture: sending a virtual message to an acquaintance, or responding to a stranger’s “hello” on the street. And then you reflect on it. It’s something you wouldn’t normally do. More than that, it’s evidence that you are capable of moving closer to becoming confident, socially capable, and even brave. And that’s when the dopamine hits, which reinforces the behaviour and the process itself. The upward spiral, the positive cycle, begins. With this framework in place, it’s not just a 1 page business plan; it is a step towards your goal of starting a thriving business. It’s not just a mediocre page; it is an iterative part of the larger, enthralling novel you can write. It is not just 5% of your pay-cheque set aside; it is a handful of bricks in the wall of your future house. So, when you are struggling to find some purpose or meaning in the grind towards your larger goal, look to the small things. Notice them, and remember them. Tell yourself: “I am on the right track.” “I am moving in the right direction.” “This is part of the plan.” “This shows I am getting better at handling x.” “If I get through this, I’ll be stronger/more resilient/more (insert adjective here).” “It’s getting closer.” The more you can reward the effort process, the better off you are at building effective dopamine reward circuits that will help you achieve your goals. And a world where you can, and do, achieve your goals will be a better place for everyone. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed